We know that learning about a medical issue can feel heavy and isolating. Many of us have sat in waiting rooms, worried about tests or what a diagnosis might mean for family life. This guide is written for people who need clear, reliable answers now.

We introduce hepatitis as a common viral infection that targets the liver and can cause either a short-term acute illness or a long-term chronic disease requiring ongoing care for many people. Some will have clear symptoms like jaundice, while others have no signs at first.

Our aim is evidence-based guidance. We will include a careful HepatoBurn review to compare supplement claims with proven care. We stress that supplements are not a replacement for vaccination, testing, or approved antivirals that form standard treatment.

Throughout, we prioritize U.S. clinical guidance and practical steps to limit spread at home and work. Ahead we will cover transmission, testing, vaccination timing, post-exposure action, and long-term management so you can make informed choices for your health.

Key Takeaways

- Hepatitis is a viral infection that can be acute or chronic and affects the liver.

- Many people have no early symptoms; testing and vaccination matter in the United States.

- Chronic disease is managed with antivirals to reduce cirrhosis and cancer risk.

- Supplements like HepatoBurn will be reviewed but are not substitutes for vaccines or antivirals.

- We focus on evidence from CDC, WHO, and Cleveland Clinic to guide practical next steps.

Why this ultimate guide to hepatitis B matters in the United States

This guide matters because it turns national policy into clear actions people can use today. We focus on U.S. guidance so readers know how policy, vaccine access, and screening shape personal risk and prevention.

In 2022 the U.S. estimated 13,800 acute infections, with adults aged 40–59 making up 52% of reported cases. Those numbers show reports undercount true spread, so we urge testing before symptoms appear.

We will also preview our supplement review to help people avoid misinformation and to stress that approved vaccination and clinical care remain primary tools to limit disease and protect health.

Below is a quick comparison of actions we recommend and the impact on families and workplaces.

| Action | Who benefits | Primary effect | U.S. guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Routine adult vaccination | Adults ≤59 years | Reduces new infections | CDC: universal through 59 |

| Risk-based vaccination | Adults ≥60 with risk | Targeted protection | CDC: recommend by risk |

| Timely testing | People with exposure | Early diagnosis, less spread | Test before symptoms |

- We explain tailored steps for work, sex, and blood exposure.

- We translate national recommendations into actions we can take today.

Key facts and the future of hepatitis B management

Global figures show how large this liver threat remains and why action matters now. WHO estimates put 254 million people with chronic infection in 2022 and about 1.2 million new infections each year.

Deaths totaled roughly 1.1 million in 2022, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer. That link between persistent infection and life‑threatening outcomes is why prevention and early treatment are vital.

Vaccination offers nearly 100% protection when the full series is completed, so access and adherence are our most direct levers to reduce risk. New 2024 guidelines may expand who qualifies for antiviral treatment, meaning more people could get care sooner.

Improved testing, better fibrosis assessment, and regular monitoring let clinicians catch progression early and lower complications. We will also debunk supplement claims in our HepatoBurn review and keep elevating proven strategies we can act on now.

“Simpler testing and wider adult vaccination could transform outcomes for millions.”

- Scale: hundreds of millions affected worldwide.

- Outcomes: chronic infection can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

- Future: guideline changes, better diagnostics, and broader vaccination offer hope.

Understanding the virus: what hepatitis B is and how it affects the liver

To make lab results meaningful, we first explain the virus and its effects on the liver. We promise clear definitions so we can interpret tests and plan care together.

Acute versus chronic: definitions we use

Acute hepatitis describes a recent infection. Symptoms may appear or not. In most adults, it clears within months.

Chronic hepatitis means the infection lasts beyond six months. Ongoing immune activity can slowly injure the liver and raise long-term risks like cirrhosis and cancer.

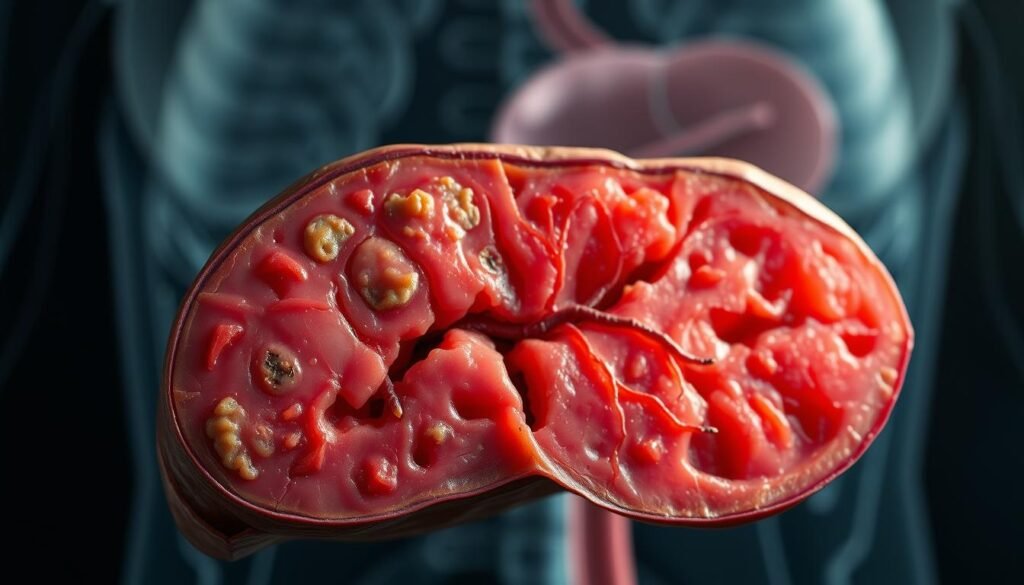

How the virus attacks liver cells

The virus enters liver cells, makes copies, and triggers inflammation. That immune response can damage tissue and create scarring over years.

- Adult-acquired infection becomes chronic in under 5% of cases; early-life infection becomes chronic in about 95%.

- Chronic infection increases risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (WHO data).

- Biology drives surveillance: viral load and liver tests tell us when to start antivirals and how well treatment works.

These definitions will guide our discussion on diagnosis, natural history, and treatment choices in the sections ahead.

hepatitis B

First, we clarify the core facts about this liver infection to guide the next steps.

The condition is inflammation of the liver caused by a specific virus. It can be an acute illness that clears or a chronic state that lasts years.

Many people carry the infection without symptoms. That is why screening is a key pillar of prevention. Early testing finds silent carriers and reduces spread.

Vaccination is safe, effective, and widely available in the United States. Completing the recommended doses prevents new cases and protects communities.

Below is a quick snapshot to keep these points clear and actionable.

| Feature | What we should know | Action for people |

|---|---|---|

| Course | Acute or chronic | Test if exposed or at risk |

| Symptoms | Often absent early | Screen even if well |

| Prevention | Safe vaccines available | Get vaccinated and encourage contacts |

Next, we look at signs we may notice and when to seek care.

Symptoms you shouldn’t ignore

Recognizing key signs helps us act quickly when liver illness appears.

Early acute illness can bring clear clues. We may notice jaundice, dark urine, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Abdominal discomfort is common too.

When symptoms escalate

Severe acute hepatitis can progress rapidly. Look for confusion, yellowing that spreads, bleeding, or swelling of the belly. These are red flags of liver failure and need urgent care.

Silent course of chronic infection

Many people have no symptoms for years. That silent course means feeling well does not rule out disease.

What we should do:

- Get tested after known exposure or if we have risk factors.

- Seek urgent care for persistent vomiting, severe fatigue, or any signs of liver failure.

- Keep routine follow-up if tests show chronic infection even when we feel fine.

| Stage | Typical signs | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Jaundice, dark urine, nausea, vomiting | Test, rest, hydrate, medical review |

| Severe acute | Confusion, bleeding, severe abdominal swelling | Emergency care, hospitalization |

| Chronic (silent) | Often none until complications | Regular monitoring, antiviral discussion |

Transmission: blood and body fluids, sex, and everyday exposures

Understanding real transmission routes lets us focus on prevention without fear. We describe how the virus travels so we can protect partners, families, and communities.

Sexually transmitted routes and partner protection

The virus is concentrated in blood and some other body fluids. Semen and vaginal secretions can transmit infection during sex.

Using condoms and barrier methods lowers risk for both partners. Testing and vaccination for both people in a relationship give added protection.

Percutaneous exposures: needles, tattooing, piercing, and sharp instruments

Transmission also occurs when skin is pierced. Reused needles, unsafe tattooing, or shared equipment can cause exposure.

Choose licensed shops, single-use needles, and verified sterilization to reduce risk.

Mother-to-child transmission at birth and early childhood

Perinatal spread is common without prevention. Timely immunization at birth and maternal care plans cut newborn risk sharply.

Breastfeeding is allowed when the infant receives recommended vaccines.

What does not spread HBV: casual contact and saliva without blood

Casual contact, hugging, coughing, or sharing utensils does not spread the virus. Saliva alone is not infectious unless blood is present.

| Route | Risk | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Blood contact | High | Avoid sharing razors, use gloves for spills, disinfect with EPA-registered agents |

| Sexual fluids | Moderate | Condoms, testing, vaccination |

| Percutaneous (needles, tattoos) | High | Single-use equipment, licensed facilities |

| Perinatal | High | Birth dose vaccine, maternal antiviral when indicated |

- Household tips: Don’t share toothbrushes or razors; clean blood spills promptly.

- Use factual, stigma-free language when discussing risk with a partner or family.

Who’s at higher risk? Groups we prioritize for testing and vaccination

Knowing who faces higher odds of infection helps us target testing and protection where it matters most.

We prioritize people with chronic liver disease and those living with HIV or hepatitis C. Coinfection raises complications and speeds progression. These people should get prompt testing and vaccine offers.

Clinicians: use a simple checklist at intake to flag risk and offer on-the-spot vaccination when appropriate.

Priority groups to test and vaccinate now

- Close contacts and partners of infected people — test and vaccinate without delay.

- People with chronic liver disease, and those with HIV or hepatitis C — prioritize linkage to care.

- People who inject drugs, men who have sex with men (MSM), and people in prisons — targeted programs break transmission chains.

- Healthcare and public safety workers with blood exposure risk — ensure occupational vaccination.

- Migrants from regions with higher prevalence — connect to testing, vaccination, and treatment services.

| Group | Why we prioritize | Action |

|---|---|---|

| People chronic liver disease | Higher complication risk | Immediate testing and vaccine offer |

| People who inject drugs / MSM / incarcerated people | Higher transmission rates | On-site screening and vaccination |

| Healthcare workers & close contacts | Occupational or household exposure | Ensure vaccine series and post‑exposure follow-up |

Key practice point: when risk factors are present, don’t delay vaccination while waiting for lab results. Offering protection now can prevent infection and reduce spread.

Diagnosis: the tests we rely on to confirm and stage infection

We walk through the tests clinicians use so you can read a lab panel with confidence.

Core serology decoded

hepatitis surface antigen (HBsAg) tells us if active infection is present now. A positive result can mean recent or long-term infection.

Anti-HBs shows immunity from past infection or vaccination. Total anti-HBc points to past or current exposure, while IgM anti-HBc suggests recent infection within six months.

Infectivity and viral load

HBeAg correlates with high infectivity. HBV-DNA measures the viral load and guides treatment timing and response monitoring.

Imaging and fibrosis assessment

We order ultrasound or elastography to stage liver scarring and plan surveillance for long-term disease.

“Clear panels let us act sooner and avoid needless delays.”

- Some results need repeat testing after a few months to tell acute from chronic infection.

- Post-vaccination serologic testing is done 1–2 months after the final dose for defined groups.

- In common clinical scenarios, we outline follow-up steps so both clinicians and people know what to expect.

The natural history: from acute infection to chronic disease

We map how a new infection often unfolds and where critical care decisions sit along the timeline.

Most adults clear an acute hepatitis episode. In fact, fewer than 5% of adults progress to chronic hepatitis after first exposure. By contrast, infants and young children face far higher odds — about 95% become long‑term carriers when infected early in life.

That age gap changes everything for monitoring and prevention. When infection persists, ongoing inflammation raises risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer over years.

Key checkpoints guide our actions: early testing after exposure, repeat serology at six months to confirm chronic status, and periodic viral load and liver test reviews to time antiviral therapy.

- Initial phase: exposure → possible acute illness; most adults recover.

- Transition: failure to clear by six months marks chronic infection.

- Chronic phases: immune‑active or inactive states tracked by labs to decide therapy.

| Stage | What we see | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure to acute | Symptoms or none; short-term liver test changes | Test, rest, follow-up |

| Unresolved at 6 months | Chronic hepatitis established | Start surveillance and consider antivirals |

| Long-term monitoring | Viral load, ALT trends, fibrosis assessment | Schedule imaging, antiviral decisions, cancer screening |

“Early vaccination in infancy dramatically lowers lifetime risk and simplifies care.”

Complications we aim to prevent: cirrhosis and liver cancer

Chronic inflammation quietly changes liver structure over years, making prevention a top priority. When inflammation persists, scar tissue can replace healthy cells and weaken organ function.

How chronic inflammation leads to scarring

Ongoing immune activity triggers fibrosis, a buildup of scar tissue. Over time, fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis, which impairs the liver’s ability to process toxins, clot blood, and store nutrients.

These are preventable complications when we act with vaccination, timely treatment, and regular follow-up.

Hepatocellular carcinoma risk and surveillance

Persistent infection raises the chance of hepatocellular cancer. In 2022 an estimated 1.1 million deaths were linked to this disease, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Surveillance programs use periodic ultrasound and targeted testing to find liver cancer earlier, when treatment improves survival. Antiviral therapy lowers the long-term risk of both cirrhosis and cancer and helps people stay well.

“Preventing infection through vaccination remains our most powerful tool.”

- Regular imaging and risk stratification guide how often we screen.

- Staying in care and starting antivirals when indicated reduces complications and improves survival.

Vaccination: schedules, doses, and lifelong protection

A simple, timely vaccine series is one of the most effective tools we have to protect newborns and adults alike.

At birth and in early months, every baby should get a dose within 24 hours of delivery. That birth dose is followed by two or three additional doses given at least four weeks apart to complete the series over several months.

Infant timing and the three-dose series

Standard infant schedules finish the series across months to build durable protection. Combination pediatric vaccines (Pediarix, Vaxelis) can simplify visits while completing required doses.

Adult options in the United States

Adults may choose a convenient two-dose vaccine series (Heplisav-B) given four weeks apart, or a traditional three-dose series (Engerix‑B or Recombivax HB) spaced over months. Twinrix offers combined protection for adults who need both hepatitis A and the other vaccine.

Post-vaccination testing and boosters

Post-vaccination serologic testing (PVST) is recommended for select groups: infants born to infected mothers, healthcare workers with exposure risk, people on hemodialysis, immunocompromised individuals, and sex partners of infected people.

Protective anti-HBs levels indicate immunity. Boosters are generally not needed after a completed three-dose series, but we follow PVST results and clinical context to guide any additional doses.

“Completing all doses on schedule maximizes immunity and moves us closer to elimination.”

| Group | Recommended regimen | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| Newborns | Birth dose + 2–3 doses over months | Routine infant visits; PVST if mother infected |

| Adults (18+) | Heplisav‑B (2 doses) or Engerix‑B/Recombivax (3 doses) | Check immune status for high-risk people |

| Special groups | Accelerated or additional dosing as needed | PVST and tailored boosters if low response |

Post-exposure care: acting within hours to reduce risk

A brief window after an exposure gives us the best chance to prevent infection. We should move quickly after a needlestick, splash, or other contact with blood or potentially infectious fluids.

Immediate actions:

- Clean the wound with soap and water and flush splashes to the eyes or mouth with water.

- Report the incident to occupational or public health so we can arrange testing and follow-up.

- Seek medical evaluation within hours for possible post‑exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

Vaccine and hepatitis immune globulin after exposure

When to give vaccine now: If the person is unvaccinated, we usually start the first vaccine dose as soon as possible. Completing the full series of doses on schedule builds protection.

When immune globulin helps: Hepatitis immune globulin is added for high‑risk exposures or when the source is known to be infected. We may give both immune globulin and the first vaccine dose to provide immediate passive protection and long-term active immunity.

- Non‑bloody saliva exposures rarely require PEP, but we still evaluate based on circumstances.

- The virus can survive on surfaces for 7+ days; clean spills with EPA‑registered disinfectants.

- Follow-up testing is done at recommended intervals (baseline, 1–2 months, and at 6 months) to confirm response and rule out infection.

“Acting within hours after exposure gives us the best chance to prevent infection.”

Treatment today: evidence-based care for chronic hepatitis B

Effective oral antivirals now let us control the virus and change long-term outcomes for many people.

Our goal is to explain standard drug choices, what they aim to achieve, and how we track results so people chronic get clear, practical guidance.

First-line antivirals: tenofovir and entecavir

Tenofovir and entecavir are the main oral treatments. Both give durable viral suppression and are recommended by leading U.S. and global guidelines.

These drugs lower viral load, reduce inflammation, and slow progression to liver disease. Good adherence matters: missed doses can weaken viral control.

Goals of therapy: suppress virus, reduce complications, improve survival

- Suppress the virus to undetectable levels using HBV-DNA monitoring.

- Reduce risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer with sustained viral control.

- Improve long-term survival and quality of life by preventing advanced disease.

When treatment is long-term and how we monitor response

Most people who start therapy continue for years, often lifelong. We decide based on viral load, HBeAg status, liver tests, and fibrosis assessment.

Monitoring typically includes labs every few months at first, then spaced out to every 6–12 months once stable. HBV-DNA guides response and detects resistance early.

| Measure | Why we check | Typical timing |

|---|---|---|

| HBV-DNA (viral load) | Assess suppression | Every 3–6 months until stable |

| ALT / liver tests | Track inflammation and liver injury | Every 3–6 months |

| Fibrosis imaging (elastography) | Stage scarring | Annually or per risk |

Supportive care helps but does not replace antivirals. Nutrition, staying current with vaccines, and avoiding alcohol lower strain on the liver.

“Antivirals slow cirrhosis, reduce cancer risk, and improve survival when used correctly.”

Note: We will review HepatoBurn claims later, but supplements are not a substitute for approved antiviral treatment or vaccination. Always discuss therapy and complementary products with your clinician.

Living well with hepatitis B: protecting our health and others

Simple routines at home and work can cut transmission odds and help us stay well together.

We offer clear, everyday steps that protect a partner, family members, and coworkers while supporting our own care and health.

Safe sex, household precautions, and workplace considerations

We practice safer sex to reduce risk for both people in a relationship. Consistent condom use plus regular testing and open communication with a partner are key.

At home, avoid sharing razors or toothbrushes and clean any blood spills promptly. The virus can survive on surfaces for days, so use proper disinfectants when needed.

- Sex: use condoms and discuss vaccination with your partner.

- Household: do not share personal grooming items; cover open wounds.

- Work: follow standard precautions and report any exposure to occupational health immediately.

Pregnancy planning and preventing perinatal transmission

We plan pregnancies with maternal evaluation and timely actions to protect newborns.

When a pregnant person has an infection, clinicians may manage viral load and ensure the infant gets the birth dose of vaccination within 24 hours, followed by the full series.

“Timely maternal care and newborn vaccination form the strongest layer of protection.”

| Situation | What we can do | Who to involve | Expected effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual relationship | Use condoms, test, discuss partner vaccination | Partner, clinician | Reduce transmission risk |

| Household exposure | Avoid sharing razors/toothbrushes; clean blood spills | Household members | Lower chance of contact exposure |

| Work incident | Report exposure, follow occupational protocols | Occupational health | Timely evaluation and PEP if needed |

| Pregnancy | Maternal care, newborn birth-dose vaccination | OB/GYN, pediatrician | Prevent perinatal transmission |

Final practice point: we encourage supportive disclosure, timely vaccination of close contacts, and routine care to keep our households and communities healthy.

Public health and prevention in the U.S.: our path to elimination

When we link vaccination and testing in everyday settings, we cut transmission and protect vulnerable people.

Global and U.S. goals align: WHO aims to end viral liver disease as a public health threat by 2030, and CDC recommends universal adult vaccination through age 59 with risk-based offers for older adults.

What that means for us: offering the first vaccine dose promptly, testing contacts, and closing access gaps lowers new infections and narrows disparities.

- We connect individual vaccine decisions and timely testing to national elimination targets.

- Priority groups need targeted outreach so that services reach people who face the highest risk.

- Partnerships—clinics, public health, and community groups—expand vaccine access in trusted places.

“Scaling up vaccination, testing, and trusted messaging will turn policy goals into fewer infections and healthier communities.”

| Action | Who benefits | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Expand adult vaccine access | Adults and older adults at risk | Lower new infections |

| Targeted outreach | Priority groups | Reduce disparities |

| Community partnerships | Clinics and local programs | Increase uptake and trust |

Our commitment is clear: accurate information, practical vaccination offers, and easy testing in trusted settings help move us toward elimination together.

HepatoBurn Review: why supplements aren’t a treatment for hepatitis B

Supplement marketing often blurs the line between support and treatment. HepatoBurn and similar products may promise liver support, improved labs, or safe natural care. These claims are not supported by major clinical guidance in the United States.

What HepatoBurn claims vs. clinical evidence:

- Marketing: rapid liver cleansing and viral clearing. Clinical guidance: chronic infection is not cured by supplements.

- Marketing: reduced viral load without drugs. Evidence: only approved antivirals reliably suppress virus and reduce complications.

- Marketing: general wellness benefits. Some ingredients may help general health, but they do not substitute for medical therapy.

Our stance: prioritize vaccination, testing, and approved antivirals

We state plainly: no supplement, including HepatoBurn, is a valid treatment. For chronic hepatitis, first‑line antivirals (tenofovir or entecavir) are proven to reduce risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer and improve survival.

Practical takeaways:

- Do not delay evidence‑based treatment while trying supplements.

- Vaccination prevents infection; testing finds who needs care.

- Discuss any supplement with your clinician; use lifestyle measures to support, not replace, medical care.

“Supplements may help wellness, but approved antivirals and vaccines remain our primary tools to protect health.”

Conclusion

Let’s pull together the core actions that help us prevent infection and manage disease for the future.

We recap what matters: how hepatitis spreads, which symptoms warrant testing, and how labs confirm an active infection. Get vaccinated if you are eligible under U.S. guidance and talk with your clinician about protection for close contacts.

Treatment matters. For chronic cases, tenofovir or entecavir are proven to lower long‑term harm. Act within hours after a sharp or blood exposure to seek post‑exposure care.

We reject supplement “cures” like those in marketing claims. Follow evidence‑based steps—testing, vaccination, and approved antivirals—to protect our health and our communities.

FAQ

What are the common symptoms we should watch for?

Early signs include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, dark urine, and jaundice. Some people develop severe acute illness with abdominal pain and confusion. Many with chronic infection feel well for years, so screening matters even without symptoms.

How is this virus spread and what exposures are risky?

The virus spreads through blood and body fluids — sexual contact, sharing needles, tattooing or piercing with unsterile equipment, and from mother to infant at birth. Casual contact, like hugging or sharing utensils without blood, does not transmit the infection.

Who should get tested and vaccinated in the United States?

We prioritize testing and vaccination for people with chronic liver disease, HIV or hepatitis C coinfection, people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, incarcerated people, health-care workers, and newborns of infected mothers.

What tests do we use to diagnose and stage infection?

We rely on surface antigen, anti-HBs, and core antibody tests, plus IgM for recent infection. HBeAg and HBV-DNA measure infectivity and viral load. Imaging and elastography assess liver damage and fibrosis.

How does the infection progress from acute to chronic disease?

Some people clear the virus after acute illness. Others develop chronic infection when the immune system fails to clear it, leading over years to persistent inflammation, scarring (cirrhosis), and increased risk of liver cancer.

What complications are we trying to prevent?

Our goals are to prevent cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma through vaccination, monitoring, and antiviral therapy when indicated.

What vaccination schedules and doses are recommended?

Newborns should receive a birth dose followed by a multi-dose series. Adults may receive two-dose or three-dose options depending on the vaccine product. Post-vaccination testing applies to some high-risk groups; boosters are rarely needed in healthy responders.

What should we do after a recent exposure?

Act quickly — within hours to days. We recommend prompt evaluation for vaccine and, when appropriate, hepatitis immune globulin plus vaccine to reduce transmission risk.

What treatments are effective for chronic infection?

First-line antiviral drugs include tenofovir and entecavir. Treatment aims to suppress viral replication, reduce liver inflammation, lower complication risk, and improve survival. Many people require long-term therapy with regular monitoring.

Can supplements like HepatoBurn treat this condition?

No supplement replaces vaccination, testing, or proven antivirals. We advise against relying on unproven products; instead, follow clinical guidance and discuss any supplements with your clinician.

How do we protect sexual partners and household members?

Use barrier protection during sex until immune protection is confirmed, ensure partners are vaccinated, avoid sharing razors or needles, and follow standard precautions for any blood exposure.

What special steps do we take during pregnancy?

Pregnant people should be screened early. If the mother is infected, newborns need immediate vaccination and immune globulin to prevent mother-to-child transmission. We plan antiviral therapy in pregnancy when viral levels are high.

How often should we monitor someone on antiviral therapy?

We monitor viral load, liver enzymes, and clinical status at regular intervals — often every 3–6 months — to assess response and detect resistance or progression of liver disease.

Does saliva transmit the virus?

Saliva without visible blood poses very low risk. Transmission requires access to bloodstream through cuts, sores, or blood contamination, so routine casual contact is not a transmission route.

How soon after vaccination are we protected?

Protection develops over weeks to months after completing the vaccine series. Newborns get immediate protection benefits from the birth dose plus subsequent doses; adults achieve protection after the full series and, for some, documented antibody testing.

What lifestyle steps help people live well with chronic infection?

Avoid alcohol, get regular medical follow-up, vaccinate household contacts, practice safe sex, and manage other liver risks like obesity and diabetes to reduce progression and complications.

Can coinfection with HIV or hepatitis C change our management?

Yes. Coinfection often accelerates liver damage and affects treatment choices. We coordinate care across specialties and tailor antiviral strategies accordingly.